An essay by Rena Roussin

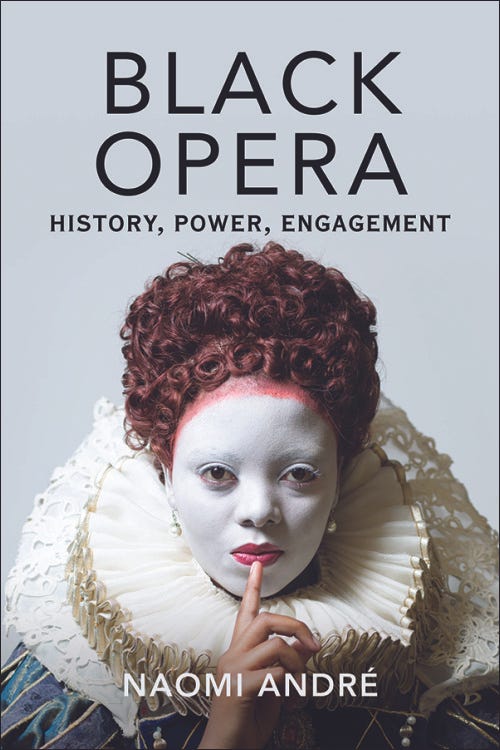

Through her concept of engaged musicology, opera scholar Naomi André stresses that opera can be “a site for critical inquiry, political activism, and social change” particularly when opera creators, producers, and audiences are willing to examine opera both “in a historical context” and “how it resonates in the present day.”

Few operas have held more lasting influence over popular culture than Carmen. From dance films to Broadway musicals to a HipHopera starring Beyoncé, the opera has no shortage of adaptations. (Notably, André draws on two adaptations and productions of Carmen, the 2005 South African film U-Carmen eKhayelitsha and Opera MODO's 2017 production, which portrayed Carmen as an incarcerated trans woman, to demonstrate her arguments).

For 150 years, the opera’s music and story have resonated across varying historical contexts and cultures. Furthermore, Carmen – and Carmen, herself – have consistently interacted with changing social understandings of gender, womanhood, and gender-based violence. Vancouver Opera’s 2024 production takes up André’s call, asking us as audience members and witnesses to consider critically how we construct and relate to gender-based violence in our contemporary society.

Gender: Constructing Carmen from 1875 to Present

In a 1986 issue of Opera News, Peter Conrad described Carmen as “an anthology of womankind no one interpreter can ever define or exhaust.”

Nearly forty years later, these words still ring true, as Carmen’s characterization shifts with changing understandings of womanhood. Initially portrayed as an anti-hero– an exoticized, disposable, and dangerous Romani “Other” – Carmen has been many things since the opera’s 1875 premiere in Paris. In an age when middle-class women were expected to – and largely did – comply with “hegemonic ideals of femininity,” Susan McClary writes, novels and operas usually either “sanitized” women as sexless, dutiful wives and mothers, or “rendered them as monstrous.” Carmen’s “unrepentant sexuality” and insistence on living her life in ways true to herself and her Romani culture rendered her firmly in the latter category. She has morphed over the years into numerous other roles, including a femme fatale, a siren, a seductress, and a victim.

In Vancouver Opera’s production, Carmen is a heroine celebrated for her agency and strength; far from a monster or a femme fatale, she is a complex and strong woman navigating a patriarchal (and often racially hostile) society. Put another way, after a long history of Carmen’s portrayal through anyone’s gaze but her own, this production seeks to engage the character on her own terms.

Carmen: The Comic

As Vancouver Opera gets ready to open our production of Carmen which runs from April 27 - May 5 at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre, we wanted to share Christopher Souza’s beautiful illustrations that he created expressly for our student study guide .

Gender-Based Violence and (De)constructing Patriarchy

When I think of the broader world of Carmen as an opera, rather than just engaging the title character, I frequently find myself thinking of Margaret Atwood’s infamous abridged quote: “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.” At the opera’s end, after Carmen mocks Don José and refuses to leave with him and return his love, he stabs her in a crazed, murderous rage. Such behaviour, regrettably, is common in opera. French philosopher Catherine Clément observed, in Opera: The Undoing of Women, that the operatic canon routinely falls prey to an “infinitely repetitive spectacle” of women who are punished – by murder, violence, loss of power, and loss of (or forced) sexuality – for threatening the patriarchal order. Even as we try to meet and celebrate Carmen on her own terms, and acknowledge realities of intimate partner violence, the patriarchy still wins in the opera’s final moments.

It is only natural for us, the audience, to want a different ending. Yet Carmen’s ending holds an inescapably important message, as pressing in our time as it was in the nineteenth century. Opera, after all, is far from the only realm where women are “undone.” Moral philosopher Kate Manne argues that gender-based violence and patriarchal social cultures are both influenced by misogynistic expectations through which men are empowered to be human beings, while women are constructed as human givers of care, attention, emotional labour, and sex. When these expectations are not met, a select minority of men may consequently “feel entitled to use, exploit, or even destroy” women’s humanity. All too often, Manne warns, as bystanders, we let them.

Throughout the twentieth century, Don José's downfall was viewed as the great tragedy of the opera, eclipsing Carmen's murder—a perspective now almost unimaginable. Carmen, once seen merely as a temptress, today stands as a potent symbol of resistance against gender-based violence. The opera's ending is fixed, but the ongoing stories of countless individuals confronting similar battles remain urgent and unresolved.

Rena Roussin is a doctoral candidate in musicology at the University of Toronto, where she studies opera's historic and current relationships to gender, disability, and concepts of social justice. As a reconnecting Métis and European settler individual, Rena is especially interested in the rise of Indigenous-led opera in Canada. An active public musicologist, she routinely writes program notes for the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, for whom she is musicologist in residence, and the Toronto Summer Music Festival. Originally from Vancouver Island, Rena is delighted to be returning to her West Coast roots by blogging for Vancouver Opera!

very enlightening article and videos, thankyou.