A Life in the Light: Bruce Munro Wright and the Philosophy of the Custodian

You can download this podcast on all major platforms including Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

In the cultural geography of Vancouver, Bruce Munro Wright occupies a position that is both ubiquitous and purposefully blurred. He is the man who is always there—showing up early, staying late, and standing just outside the spotlight’s glare. To track his influence is to map the city’s creative bedrock: from the boardrooms of the Vancouver Art Gallery to the front rows of the Queen Elizabeth Theatre, where he is known to attend upwards of forty performances a season.

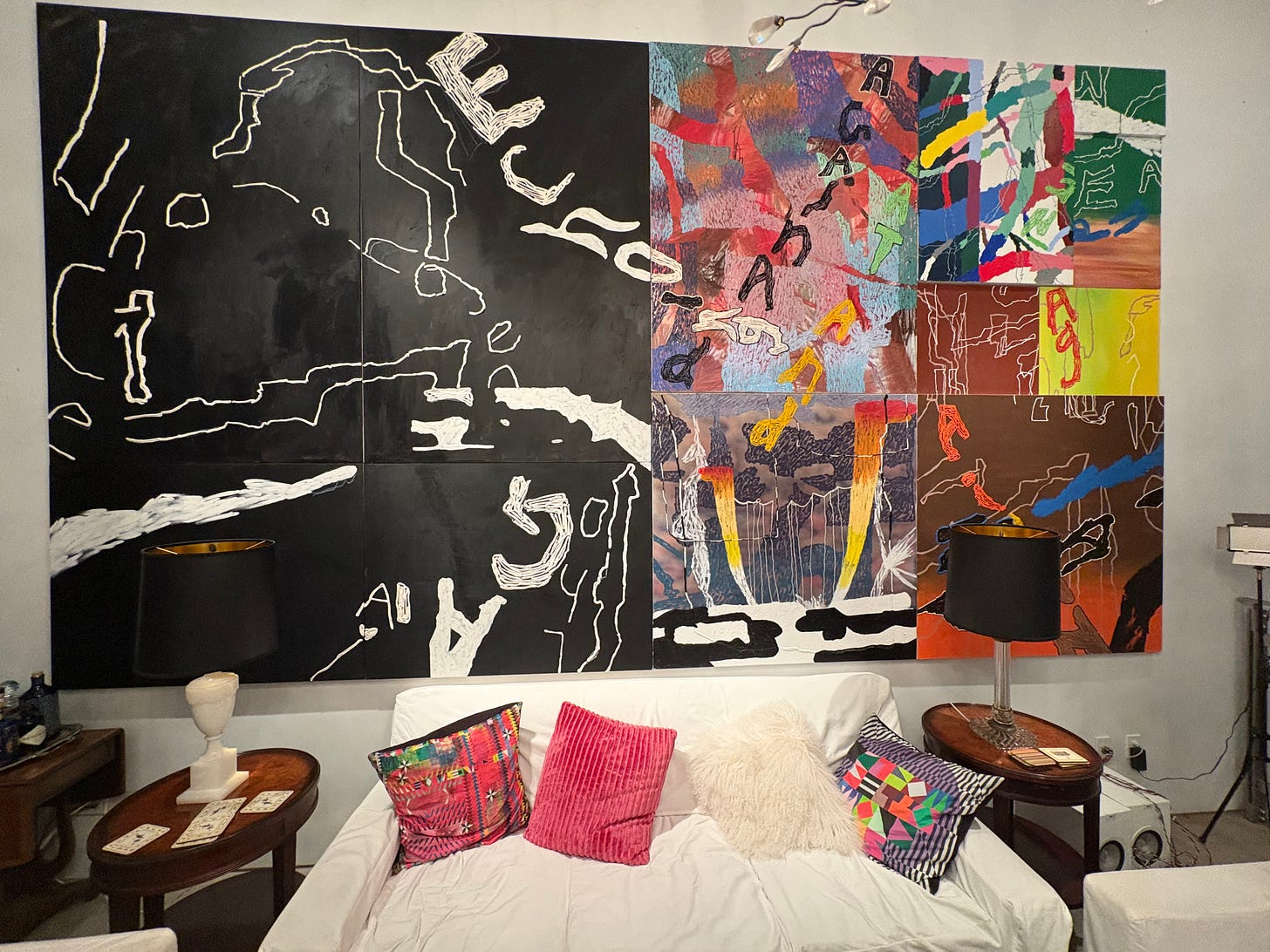

There is a certain modernist poetry to the way Wright inhabits the city. He resides in the “Choklit” townhomes, an Arthur Erickson masonry landmark built on the site of an old Purdy’s factory. It is a space famously dense with art—a private museum of B.C.’s visual history—yet Wright speaks of his collection with the detached grace of a librarian. “I don’t own art,” he says, a phrase that has become a sort of governing mantra for him. “I am only a temporary custodian of it.”

The Literacy of the Landscape

This philosophy of impermanence—the idea that beauty is something to be held in trust rather than possessed—is the key to understanding Wright’s “second act.” After a long career in law, a profession built on the rigid definitions of property and title, Wright did not retreat into a quiet sunset. Instead, he chose a full immersion into the service of the arts, effectively trading the courtroom for the wings of the stage.

The roots of this visual literacy go back to a childhood in Victoria, painting landscapes alongside a great-aunt who was a contemporary of the Group of Seven. She taught him that art was a domestic presence, a neighbor rather than a monument. While other children were learning the world through textbooks, Wright was learning it through the adventurous, sometimes veering-into-the-abstract strokes of a landscape painter’s brush.

When he eventually moved to Vancouver, that early training manifested in a hunger for discovery. His first major acquisition was a piece by Philippe Raphanel, one of the “Young Romantics” from Emily Carr. It was a large, abstracted work titled Blue Urban Tree, a study of a tree in a snowstorm rendered in deep purples and blues. For Wright, this wasn’t just a purchase; it was an investigation into the romanticism of the West Coast. Today, he treats a painting by Russna Kaur with the same inquisitive spirit, hosting a conversation with the work for a few years before passing it on to a public institution.

The Dido Frequency

If his visual eye was shaped by the landscape of the island, his ear was tuned at the Royal Conservatory in Toronto. It was there, as a young pianist and French horn player on a scholarship once held by Glenn Gould, that Wright encountered the ghost that would follow him for the rest of his life: Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas.

The emotional weight of “Dido’s Lament” became a permanent frequency in Wright’s internal soundtrack. Decades later, that teenage encounter took physical form in a harpsichord commissioned from the Vancouver maker Craig Tomlinson. A meticulous replica of a 1792 Tasker instrument, it is a marvel of 18th-century engineering reborn in the 21st.

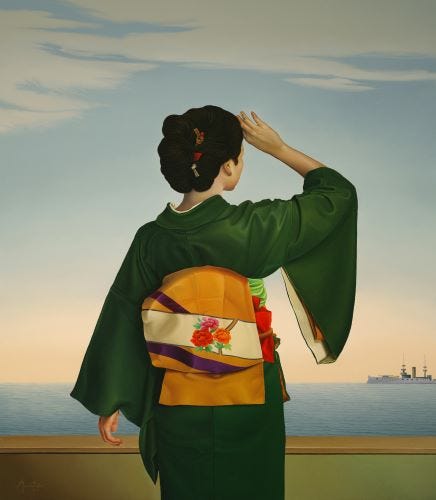

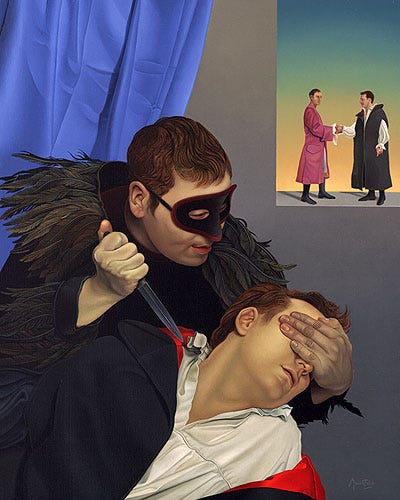

However, the instrument’s true soul is found under the lid. Wright spent a year working with the artist Marco Tulio—the visionary behind many of Vancouver Opera’s most iconic season posters—to have the interior hand-painted with scenes from the Purcell opera. It is a functional masterpiece, but for Wright, it is also a bridge between the student he was and the patron he became.

Today, the “Wright Harpsichord” is an international celebrity in its own right; opera houses from London to Berlin frequently request images of Tulio’s lid painting to grace their own programs, a testament to how one man’s private passion can fuel a global aesthetic.

The Architecture of Survival

But behind the beauty of the Choklit townhomes and the resonance of the harpsichord lies a pragmatic, legalistic anxiety. Wright, who has chaired everything from the Vancouver Art Gallery to the Vancouver Opera Foundation, is acutely aware that the survival of culture in Vancouver is currently a precarious affair.

“It’s always been scary, but it is very scary now,” he admits. In his view, the Canadian model—a delicate tripod of ticket sales, government grants, and private philanthropy—is under unprecedented strain. He speaks frequently of “angels”—the small, vital number of donors on whom entire institutions often rest. He understands the math of the arts with a lawyer’s precision: ticket sales often account for barely a third of the budget. Without the “angels,” the music simply stops.

His dream for Vancouver is one of infrastructure and intimacy. He harbors a specific, quiet ambition for a “jewel box” opera house, modeled after the world-renowned Wexford Opera House in Ireland. In Wexford, the theatre is a dense, high-performance space where the human voice doesn’t have to fight the room. Wright believes Vancouver deserves such a sanctuary—a place where the “un-amplified human voice” can achieve its full emotional height.

In 2022, Wright received the Order of British Columbia, a formal recognition of a life spent holding the room open for others. But as he nears the end of his conversation with Ashley, he seems most interested in the concept of disappearance.

He imagines a stranger decades from now—sitting in a theatre, attending a gallery opening, or listening to a care-home concert that he helped make possible. He hopes that stranger feels the power of the art, but he has no desire for them to find his name on a brass plaque.

“I don’t really care whether they know my name or not,” he says. “I just hope they enjoy the art, and then maybe be motivated to keep building our culture themselves.”

It is the classic Wright stance: the temporary custodian who ensures the music continues, then quietly exits the room before the applause begins. He has lived his life inside the light, but he has always been careful to make sure that the light falls on the art, and never on himself.

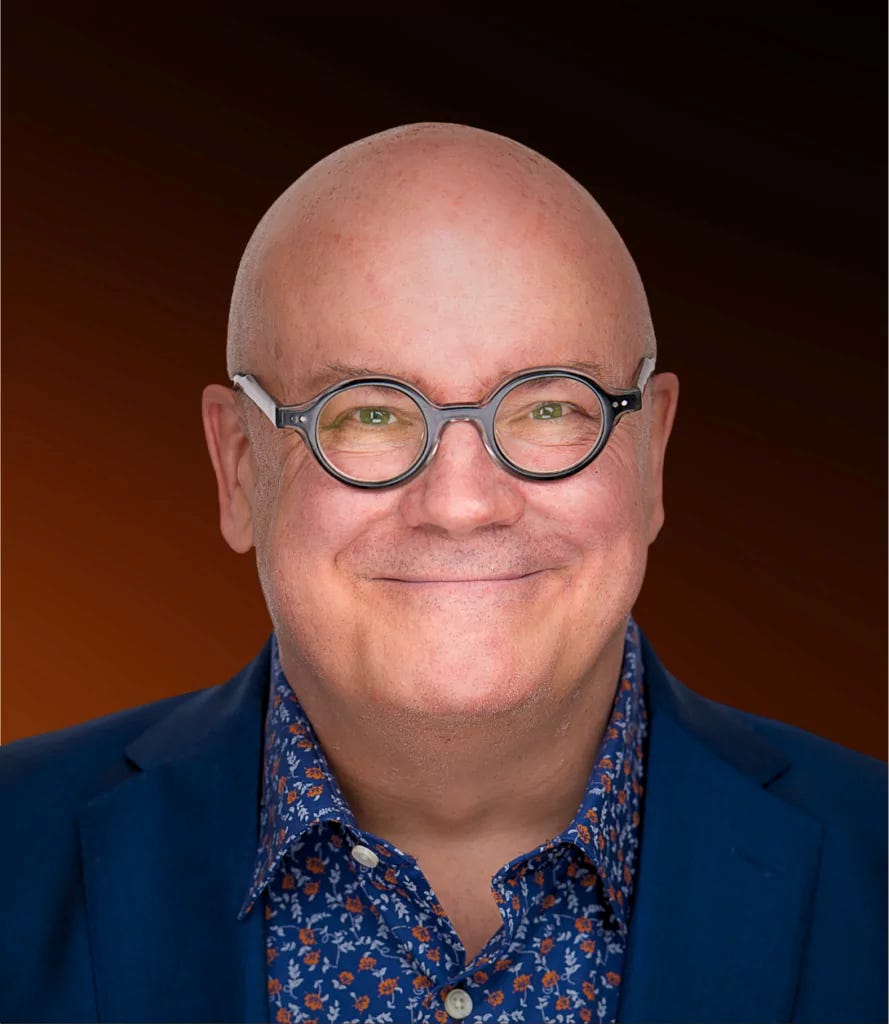

Bruce Munro Wright

Bruce is a volunteer leader in the Canadian charitable sector as board chair, director, panelist, juror, fundraiser, and philanthropist. Following retirement in 2018 from law practice, Bruce now spends full-time on charitable roles. In 2022 he received the Order of British Columbia for his arts and non-profit work. Bruce has held numerous positions in the arts world, including chairing Vancouver Opera, Vancouver Art Gallery, Health Arts Society (Concerts in Care), Pride in Art Society and Co-Chairing Capture Photography Festival. He has also Co-Chaired Splash Art Auction for Arts Umbrella for seven years, as well as special events for Vancouver Opera, Chor Leoni, and Museum of Contemporary Arts Toronto. He is a director of the Glenn Gould Foundation, Chor Leoni Foundation, and Opera in Canada, is a past director of Ballet B.C and the VSO, and is actively involved with Early Music Vancouver.

Ashley Daniel Foot - Host, Inside Vancouver Opera

Ashley Daniel Foot bridges the gap between the stage and the city through insightful, deep-dive conversations. Currently serving as Director of Engagement and Civic Practice at Vancouver Opera, he curates the multidisciplinary TD VOICES series and leads the City of Vancouver’s Arts and Culture Advisory Committee, ensuring storytelling and civic responsibility remain at the heart of the opera.

Mack McGillivray - Producer, Inside Vancouver Opera

Mack is a multimedia producer, creating shows for radio and podcast. He is passionate about cultivating local community and a lifelong lover of opera.

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. Such a profound take on ownership and stewardshp.

Exceptional piece on the notion of temporary custodianship. Wright's framing that he doesn't own art but holds it in trust cuts through alot of the ego that typically comes with collecting. The parallel betwen his legal training and this philosophy is subtle but powerful because property law is usually about permanent ownership but he's opted for impermanence. That Wexford model for an intimate opera venue sounds like a practical vision worth pursuing.