Georges Bizet: Life and Times

Dive into our seven-part series exploring the life of Carmen's iconic composer

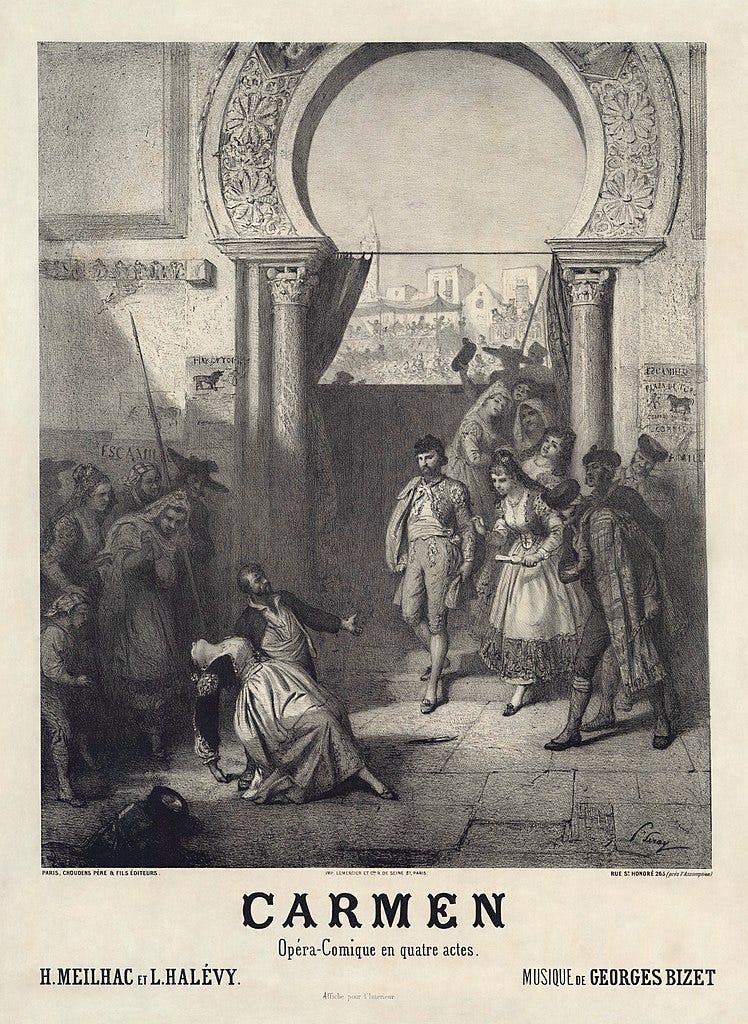

In anticipation of our production of Carmen, we are rebroadcasting our seven-part series on the composer’s life as one episode.

Vancouver Opera presents Carmen at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre from April 27th to May 5th. For tickets and more information visit VancouverOpera.ca.

Originally aired in October of 2022 ahead of our production of The Pearl Fishers.

You can also download the podcast on all major platforms including Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Act I

Act II

Act III

Act IV

Act V

Act VI

Act VII

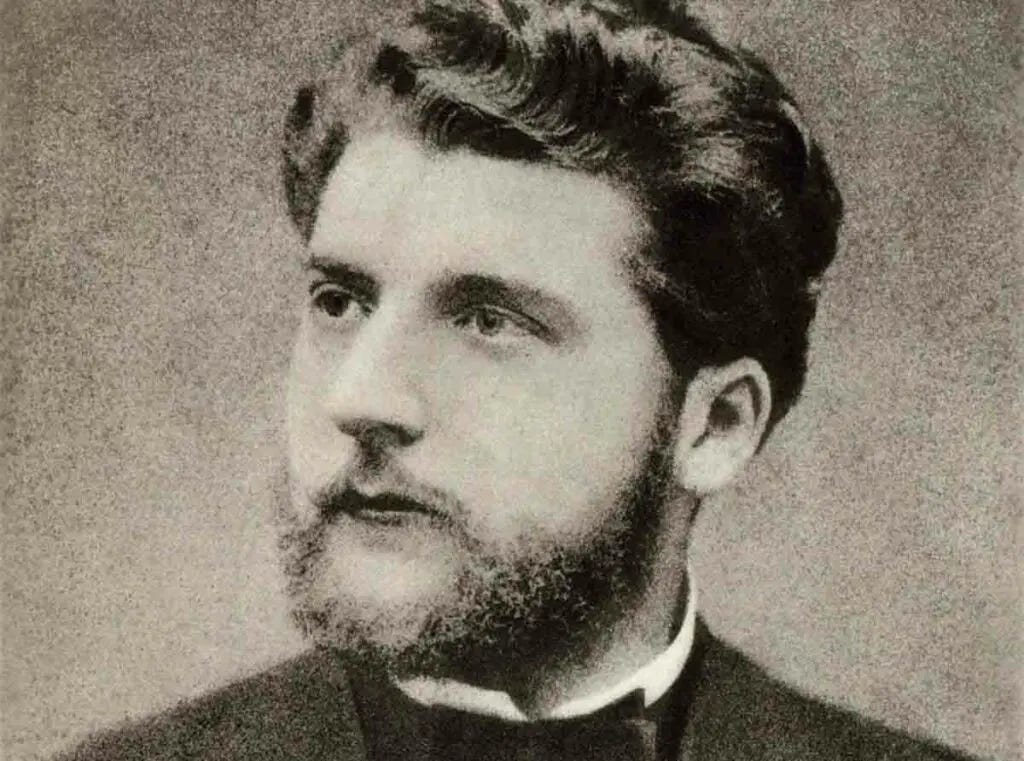

Welcome to Inside Vancouver Opera. My name is Ashley Daniel Foot. Did you know Georges Bizet, the composer of Carmen, was a musical prodigy who started composing at the age of 9?

Today, The Life and Times of Georges Bizet. This is a rebroadcast of a series we released last year, but today we are playing it for you in its entirety. Written and edited by Kris Epps, with Felix Leblanc as the voice of Georges Bizet, narration by Jane Potter, and additional voices from Ashley Daniel Foot, Travis Baugh Allen, Vincent Huynh, and many others.

Act I

The year is 1838. The Industrial Revolution is winding down and the great Gold Rush is on the horizon.

In Morristown, New Jersey, Samuel Morse—of the famed Morse code— is giving the first public demonstration of his new invention, the telegraph.

An ailing Frédéric Chopin, wintering on the Mediterranean with his lover, the writer Georges Sand, is hard at work on his 24 Préludes for piano.

Over in England, royalists are celebrating the coronation of their new Queen -Victoria;

While others queue for the first installment of Charles Dickens’ new novel—Nicholas Nickleby.

And across the English Channel on October the 25th, the composer Georges Bizet is born on a bustling street in the famous Montmartre district of Paris.

He was born Alexandre Cesar Léopold but two years later was baptized ‘Georges’. It was by this name that he was known to his family and friends for the rest of his life.

His father, Adolph Bizet, descended from artisan stock in Rouen—capital of the northern French region of Normandy. Until his marriage in 1837, he made his living as a hairdresser and wig maker.

He then became a singing teacher and a modest composer–writing a handful of compositions that are now long forgotten.

Georges’ mother, Aimée Delsarte, also came from a musical family. By all accounts she was a highly intelligent, eccentric woman as well as a talented pianist. Her letters to Georges—her only child—paint a picture of a homely, affectionate and doting mother—despite her life-long struggles with chronic illness.

It was his mother who gave Georges his first piano lesson. Having the good fortune of having hailed from a musical household, he learned notes at the same time as letters.

As with all child prodigies, stories abound of their youthful displays of genius and exceptional skill. George was no exception.

He spent many an afternoon with his ear pressed against his father’s studio door, listening with great fascination to him giving voice lessons.

One afternoon, Adolph called his young son into the room and asked him to sing a piece—at sight. To his astonishment and sheer delight, Georges began to sing the piece he’d just heard, not only perfectly in-tune but completely memorized.

Having lofty ambitions–as well as acknowledging his own limitations– it was the Conservatoire on which Adolph set his sights firmly for his young son.

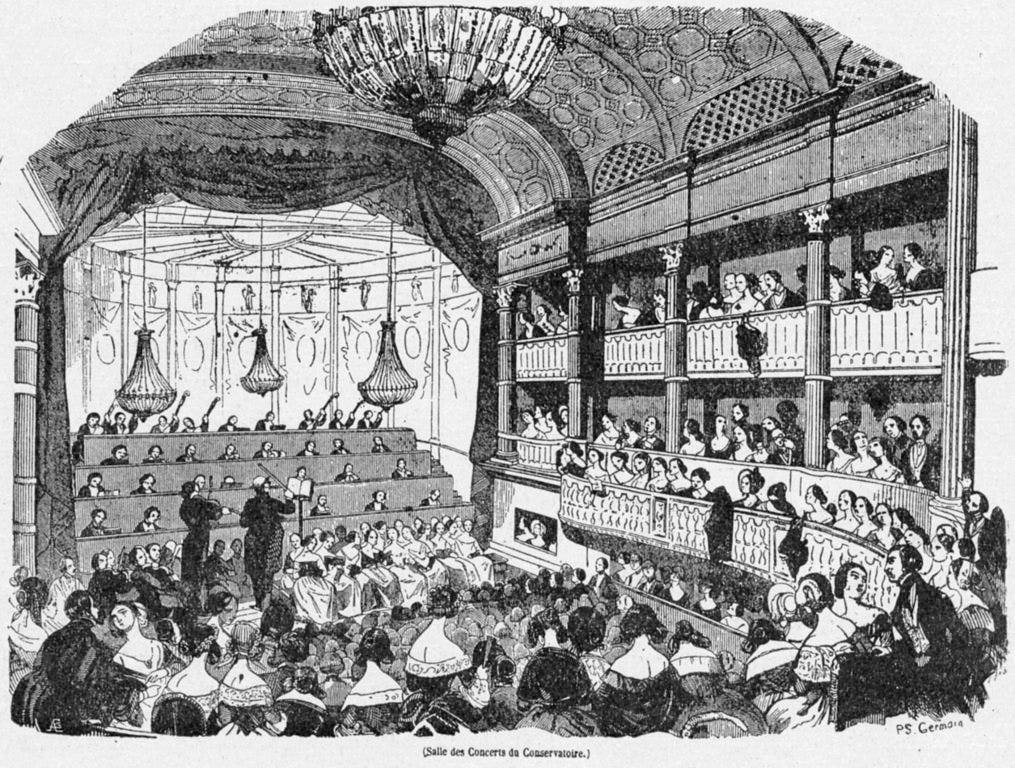

The prestigious Conservatoire de Paris was founded in 1795. An institution steeped in French music tradition, it boasts amongst its former students a wealth of French musicians. Hector Berlioz, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Gabriel Fauré have all left their indelible marks on its rich musical heritage.

Adolph’s only concern was that Georges, at 9 years old, did not meet the minimum age of 10 for enrolment at the Conservatoire. Never one to cede, Adolph went to see Joseph Meifred, a prominent horn player and member of the committee of studies—to see what could be done. When presented with the boy, Meifred was skeptical:

Meifred: “Your child is very young!”

Adolph: “True, but if he is small in stature he is big in knowledge.”

Meifred: “Really?? What can he do?”

Adolph: “Sit down at the piano, strike some chords and he will name them without a mistake.”

**CHORDS**

Georges: F-sharp minor 7th, sir”

Meifred: “You, my boy, will go to the Conservatoire!!”

On October 9th, 1848, two weeks before his tenth birthday, Georges entered the Conservatoire de Paris; everyone unaware that this eager and precocious young boy would one day change the very course of opera as we know it today.

Act II

Barely six months after his admission to the Conservatoire, Georges had already made a sizable impression, attracting the attention of Pierre Zimmerman, the Conservatoire’s former professor of piano, who agreed to come out of retirement to teach him counterpoint and fugue.

When Zimmerman fell ill, it was none other than the great French composer Charles Gounod who took over the boy’s training. Here began a musical admiration and lifelong friendship which had significant effects on Georges' musical style.

At the age of twelve, Georges entered the piano class of Antoine François Marmontel. He had great admiration for his teacher, later writing:

“In your class one learns something besides piano; one becomes a musician.”

Although famed as a composer, Bizet’s skills as a pianist are not to be underestimated. He was a brilliant virtuoso–and later became an equally skilled organist.

1853 saw new musical horizons for Georges. The fifteen year old entered the composition class of Fromental Halévy. Halévy, himself a composer of opera, was to become a prominent figure in Georges’ life. In fact, the entire Halévy family became a source of great inspiration, joy and oftentimes misery for the young composer.

Halévy’s brother, Léon, and his nephew, Ludovic were both Bizet’s librettists later in his career. And Georges would marry Halévy’s daughter, Geneviève, sixteen years later.

Many of Georges’ early compositions are preserved at the Conservatoire. His most significant work from this period was his First Symphony, which ultimately became his only foray into the traditional symphonic realm.

A delightful work in C major, Georges began writing the symphony just four days before his seventeenth birthday. Ever the expeditious worker, it was completed only one month later. Not uncommon of the times, the work was never published and did not come to light until its first performance in 1935. It has since become a perennial favorite for orchestras around the globe.

Around the time of his first symphony, Halévy deemed George ready to compete for the esteemed Prix de Rome—a French scholarship for composition students offering a five year pension to study in Rome and other prominent European musical centers: a highly desirable financial freedom for any budding composer as well as the highest honor France can bestow upon a young artist.

As time went on, Bizet found himself a part of the inner circle of French musicians, often attending the Friday night parties of Jacques Offenbach–the French operette king. It was there that he met the famous Giacomo Rossini, who at the time was the toast of the Paris opera scene.

Bizet had great admiration for the sixty-two year old master, saying:

“Rossini is the greatest of them all, because, like Mozart, he has all the virtues.”

Rossini was kind to the young composer and presented Georges with a signed photograph as well as cordial letters which Georges used on his forthcoming travels in Italy.

It is now 1857. The Prix de Rome weighed heavily on Bizet’s shoulders. The committee was offering two prizes that year. The top winner, or the laureate—would receive the full five years pension; the runner up—a four year’s pension.

The jury, selected from the musical section of the Academie des Beaux-Arts, had difficulty making their decision, vacillating between Bizet and another promising musician. Ultimately, Georges was unanimously awarded the first prize.

Crowned with the country’s highest artistic distinction as well as a brilliant Conservatory career, Bizet is now off to Rome. But he knows all too well the Prix de Rome is merely a stepping stone offering few advantages after the five-year pension; very little help in getting his works performed and certainly no guarantee for a favorable reaction from the fickle French public.

In the words of his teacher and mentor Charles Gounod:

“Now your real artistic life is going to begin—a serious and severe life it is.”

Act III

At the advanced age of nineteen, Bizet has won the prestigious Prix de Rome and is now setting off to Rome where he will spend the next three years in deep self discovery, basking in the Italian landscape and dedicating himself to his true passion.

But with great honor comes great responsibility: winners are required to submit one major composition each of the five years. These works—called ‘envois’ —are to be submitted to the Académie des Beaux Arts. In return, two critiques are issued: one for publication and one for the artist personally.

Georges left Paris the 21st of December 1857 on a route would take him through Lyons, Vienna, Valence, Avignon, Nice, Pisa and Florence before landing in Rome. His letters are full of delightful observations of the visual splendors along the way:

“It is a magnificent country. The spectacle of nature is something unknown to me. I find it impossible to analyze my impressions. An artist ought to profit by it, be he painter or musician, sculptor or architect.”

Arriving in Italy early in the new year, his impressions were….less than favorable. Despite the love for the scenery, he was mostly disgusted by the architecture:

“Churches painted like monuments in cardboard”

…and with the people, whom he perceived to be all priests and beggars:

“the Piedmontese have several ways of begging—humbly by day and with a blunderbuss by night.”

The Paris convoy of artists arrived in Rome on January 27th. Living a communal life, they made their home at the French Academy, hosted at the Villa Medici: a 16th century monastery standing high on Mount Pincio, overlooking Rome and all its grandeurs.

Given Bizet’s nature, it was not long before he acquired social success. Within a month, he had triumphed as a pianist; attended masked balls; dined with the Russian ambassador and was up to his ears in private invitations.

Never spoiled by social success, he was always aloof from his actions. On one occasion, after drawing a particularly enthusiastic ovation at an evening salon performance, his reaction was lackluster:

“It is only fair to say that there are no pianists in Italy, and if you can play the scale of C major with both hands, you pass for a great pianist.”

Fellow pensioners were more than a little jealous of Bizet’s popularity; but he paid no heed—his opinions were already well formed:

“I have success in living very peacefully with fifteen of them; the other five are utterly ridiculous, as I keep telling them to their considerable irritation.”

Regardless of his youthful preconceptions, Bizet possessed a special gift for friendship. Despite his hair-trigger temper and disdain for deception, he demanded and gave complete frankness and loyalty, and was always swift to withdraw any harsh remark or unfair judgment.

It was one month after his arrival In Rome that he began work on his Te Deum—his only sacred work aside from his Ave Maria. The motivation for the work was the Rodriguez Prize: a competition for new religious works open to Prix de Rome winners.

He began in February, 1858 and finished in May. The manuscript survives but it was not performed until 1970. Bizet—a self-proclaimed atheist—had no feeling for sacred music. His reaction to his new composition was ambiguous:

“I don’t know what to think of it. Sometimes I find it good, sometimes detestable. What is certain is that I’m not cut out to write religious music. I shall send an Italian opera in three acts, I like that better”

In the end, he lost the prize…. to the only other contestant.

With his first ‘envoi’ deadline fast approaching, Bizet searched high and low for a suitable text. Sifting through “all the libraries in Rome and reading 200 pieces!” he finally found what he was searching for in a used book stall in a back alley. It was the Italian farce Don Procopio by Carol Cambiaggio. Bizet was thrilled:

“I am decidedly built for ‘la musique bouffe’, and I lose myself in it completely. On Italian words one must write Italian music. I have not tried to cast off this influence.”

It was the Academy’s rules that all winners submit a sacred work as their first envoi. Always one to challenge authority, Bizet completed and submitted his new two act opera, Don Procopio. With no mention of his defiance, the Académie’s reviews were favorable:

“In short, Don Procopio is distinguished by an easy and brilliant touch, a youthful and bold style, precious qualities for the genre of comedy, towards which the composer shows a marked propensity. These qualities open the way to novel efforts, and M. Bizet will not forget the obligation he has undertaken as much towards himself as towards us.”

Bizet felt encouraged:

“I feel more confident than ever, though I don’t conceal from myself the immense progress that remains to be achieved before I get anywhere, but I have good hopes.”

Ever the disciplined artist, he immediately set to work on his next two submissions. With a second wind of ambition, his intentions were to write a musical setting for Victor Hugo’s Esmeralda as well as another symphony. But as was often the case in his life, the best laid plans of mice and men often went awry.

He began to experience severe doubts, questioning his abilities to compose. He had gone from working fluently with little vision and great imagination, to paralyzing self doubt. In a letter to Gounod, he explains:

“I flounder a lot and progress little…I have always been very much the student; it is not easy to become one’s self. I mistrust my facility: I have around me ten intelligent fellows who will never be more than mediocre artists, and all because of the fatal confidence with which they abandon themselves to their cleverness. Cleverness in art is almost insensible, but it only ceases to be dangerous the moment the man and the artist find themselves.”

Few compositions projected in Italy by Bizet ever reached completion. In fact, this was true throughout his entire professional life. He spent the next few months vacillating between works, endlessly contemplating the best artistic path forward.

His planned symphony was now to be his second envoi but after several weeks it went into the fire. Abandoning Hugo, he set to work on his choral symphony Vasco de Gama for his second ‘envoi’—and he was very pleased:

“Whatever a gentleman of the Academy say, my opinion is formed, and it is good, very good even.”

It was in July 1860 that Bizet left Rome with his friend Guiraud. The three years had been the happiest of his life. He adored the climate and the countryside; the character of each street and the second-hand bookshops; the museums and the art galleries:

“I shall cry murder if a single piece of art is removed!”

Bizet did not want to leave. He had an emotional sendoff. People he never cared for shook his hand with tearful eyes.

“I had a frightful attack of nerves! I wept for six hours straight off. I realized that I was liked at the Academy, and that was very moving.”

His travel diary shows a young man eager to sample all of life’s offerings. He writes of architecture, painting and sculpture; of playing organ at churches along the way and of his insatiability for prostitutes.

It was on this return journey that the germ for his Roma Symphony was born—a work that would consume most of his life:

“I have in mind a symphony which I would like to call Roma, Venice, Florence and Naples. That works out wonderfully: Venice will be my andante, Florence my scherzo and Naples my finale. It’s a new idea, I think.”

Upon arriving in Venice, Bizet received a letter from his ailing mother, which sent him into a fit of despair. It was inconceivable to him that he may lose the very being that he most needed at the onset of his career. The mere possibility of being deprived of his mother’s nurturing and guidance led his already mercurial nature down an even darker path.

The duo decided to end the tour and return to Paris immediately, hoping the cruel fate of time was on their side.

Act IV

When Bizet returned to Paris in 1860, France was in the throes of the Second French Empire: an eighteen-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III which spanned from 1852 – 1870. This made life challenging for all professional musicians.

The only open road for a contemporary composer with serious ambition and without private means was almost exclusively the stage.

At the time, there were two permanent opera houses in Paris. The Opéra, regarded as the premier national theater; and the Opéra-Comique. Opera had originally been an aristocratic form of art and it was at the Opéra that this tradition endured—although heirs of the French Revolution had made great effort to bring it within the comprehension of the middle classes.

The Opéra was little more than a salon for snobs—the audience more interested in the latest fashions than the performance. The attitudes struck against their own composers were most telling: for almost three centuries, the accepted music in France was exclusively composed by foreigners: Lully in the 17th century; Gluck in the 18th and Rossini in the 19th century.

Although only marginally better, the Opéra-Comique was more supportive of native talent. With its clear, elegant, polished and often vulgar music, it was designed to cater to the Paris bourgeois. It had originated over a century earlier as a parody of the tragic stage. At the time, neither theater was in a state of healthful growth, placing profit ahead of art at every opportunity.

Outside of these two state theaters were the Théâtre Lyrique, mostly successful with revivals of foreign works translated into French; and the Théâtre Italienne, which fed the craze for Italian opera and operetta–over which, by 1850, Jacques Offenbach reigned supreme.

The Prima Donnas of the day were another great source of consternation for every young composer. The stories of their capacity to exert artistic control over every aspect of the production are legendary.

It was fully expected that the composer would adapt their musical style to suit the particular singer. Failure to accommodate would often result in a very public ostracizing.

The attitudes of the directors were little better as their goals were purely financial. They regarded the opera score not as a piece of art, but as material they could manipulate and present in the most lucrative way.

Yet another problem was the highly inflammatory and deplorable level of the musical criticism. At every opportunity, critics displayed prejudice, conservatism and ignorance.

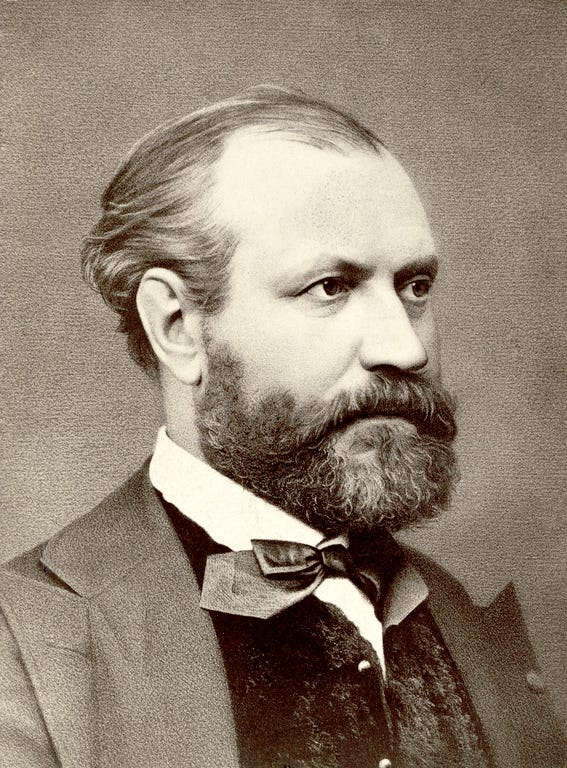

Camille Saint-Saëns, a contemporary and lifelong friend of Bizet, quotes one of the most brilliant reviews by Theophile Gautier, a prominent music critic of the day:

“Our real duty—and it is a true kindness—is not to encourage these composers but to discourage them. What use is it to encourage them and their efforts when the public obstinately refuses to pay any attention to them?”

With the lingering illness and ultimate death of his beloved mother in 1861, Bizet fell into a deep depression. In a letter to a close friend, he related a dream—which provides a glimpse of his psychological state of mind:

“At night I would feel a terrible agony, I would be forced to throw myself down in an armchair, and then I would think I saw my mother coming into the room. She would cross and stand beside me and put her hand on my heart. Then the agony would increase. I would suffocate, and it seemed to me that her hand, weighing on me so heavily, was the true cause of my suffering.”

Shortly before his mother’s death, he told Gounod that he was conducting two love affairs. One was with his parent’s maid, Marie Reiter, who produced a son, Jean in 1862. Marie remained dedicated to the Bizets, nursing Georges during his last illness.

The death of his mother at age forty-five induced a life-long fear of his own premature demise. Suffering from angina since the age of fourteen and having regular attacks of articular rheumatism, he would often be bedridden with painful joints for weeks on end.

Despite his recent trials and tribulations, he managed to finish his third envoi in the autumn of 1861—one year late. He had intended to submit a symphony—likely the Roma symphony he had projected a year earlier in Rome; however, his work was interrupted with the death of his mother. Instead, he submitted two movements: the scherzo and the funeral march with a supplemented overture. All were met with rave reviews.

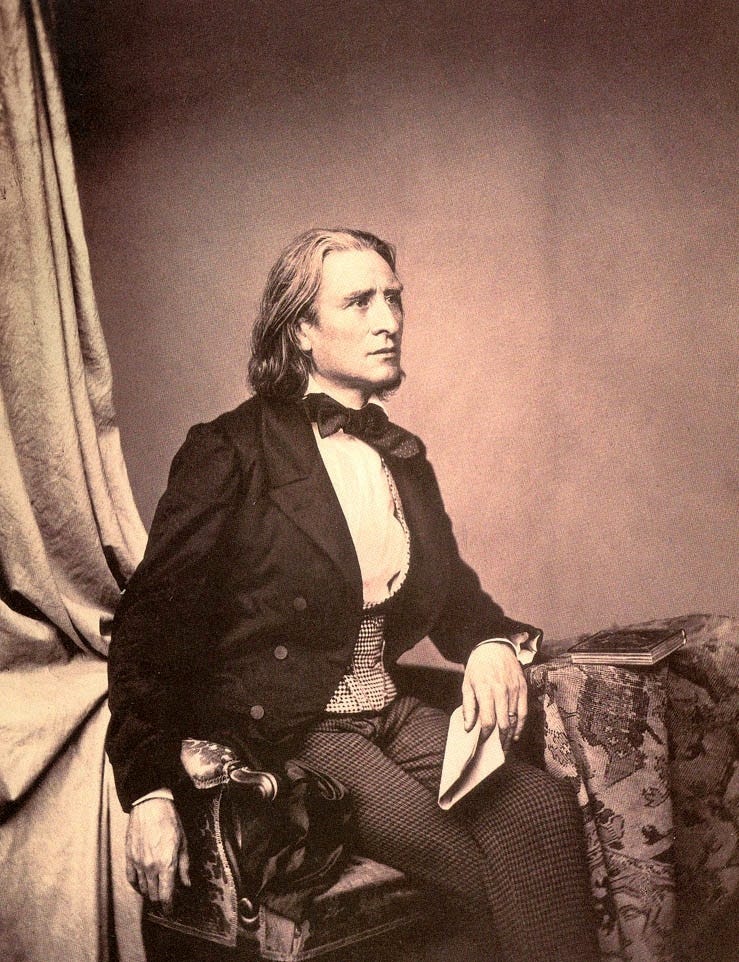

A fascinating anecdote from 1861 has Bizet’s power and temperament on full display. One evening, he attended a dinner party of his former teacher, Halevy, the great Franz Liszt was also in attendance.

After dinner, Liszt was persuaded to delight the company with one of his latest compositions. Naturally, its appalling difficulties and pyrotechnics rendered the crowd speechless. Being congratulated on his work and effortless execution, Liszt replied in kind:

“Yes, it is a difficult piece, horribly difficult, and I only know two pianists in Europe capable of playing it as it is written and at the speed I desire: Hans von Bülow and myself.”

Recalling Bizet and his extraordinary memory, Halevy played a few chords on the piano, attempting to emulate what Liszt had just played, saying:

“Did you notice this passage, Georges?”

Bizet proceeded to play the whole passage—from memory. Duly impressed, Liszt then produced the manuscript, at which point Bizet played the entire work—without mistake or hesitations. Liszt took him by the hand, declaring:

“My young friend, I thought there were only two men able to surmount the difficulties with which it was my pleasure to adorn this piece. I was wrong: there are three, and in justice I should add that the youngest of the three is perhaps the bolts and most brilliant.”

The retiring Minister of Fine Art, Count Walewski had recently given the Théâtre-Lyrique a grant of 100,000 francs on condition that every three years a three-act opera was to be written by a young winner of the Prix de Rome. It was Bizet’s good fortune that he was the first to benefit under this new scheme.

Leon Carvalho, the director of the Théâtre-Lyrique, had met Bizet and, smitten by his charm and talent, offered him the libretto to Les Pecheurs de Perles—The Pearl Fishers.

Bizet eagerly signed the contract in April of 1863. The production was fixed for mid September, giving him precious little time. He delivered the score in early August and the opera premiered on September 30th.

It received a rather tepid reception. Bizet was greeted with enthusiastic applause and, according to one account, was “a little dazed; his head was lowered and revealed only a forest of thick curly hair above a round, still rather childish face, enlivened however by the quick bright eyes which took in the whole hall with glances at once delighted and confused.”

The tone of the press, however, was frigid and patronizing. He was accused of “harmonic bizarreries born of a misdirected search for originality. An orgy of noise”.

It was only the composer and respected critic Hector Berlioz who praised the work, writing that:

“The score of Les Pechers de Perles does M Bizet the greatest honour, so that we shall be forced to accept him as a composer despite his rare talent as a sight-reader.”

Unfortunately, even Berlioz’s positive appraisal did not spare Les Pechers de Pearles. The opera failed with the paying public and was only given eighteen performances. It was not played again until 1886, at which time Bizet was both world famous, and dead.

Act V

At the age of twenty-four and with his Prix de Rome pension finally expiring, Bizet was now both financially and artistically insecure, having to resort to meaningless and often-times demeaning work.

Regardless, his output was astonishing. He speaks of working sixteen hours a day—experiencing frequent periods of exhaustion. Most nights were spent writing opera piano transcriptions as well as orchestrations of hit songs of the day.

He was also rehearsal pianist for the Opéra Lyrique but still made time to have his patients frayed by talentless, middle-class piano students who wanted nothing more than to play pretty salon pieces.

It is important to remember Bizet not only as the brilliant stage composer that he was, but also the great pedagog that he became. One of his early students, Edmond Gilbert, left a revealing and precise account of his brilliant teachings.

When asked what books he had read, Bizet was delighted when Gilbert’s list included his idols, Goethe and Schiller:

“That settles it. People think you don’t need any education to be a musician. They are wrong; you have to know a great deal.”

The subject of fees made him adamant:

“Don’t ever mention that again. I give lessons for money because they bore me. With you, we are simply talking of things that interest us, things that we love. We are swimming in the same water.”

Galabert paid Bizet with wine from his father’s vineyard.

As a teacher of composition, he was no less opinionated:

“Let yourself go, aim at the emotions, avoid dryness. Let us have fantasy, boldness, unexpectedness, enchantment—above all, tenderness, morbidezza!”

On orchestration:

“No, no, no: that lacks air! And in orchestration you must have air! Let each part have around it sufficient room to move.”

When discussing the stage, his true passion, he could elaborate for hours.

“It is the composer's obligation and sole duty to enter the skin of each character and interpret their inner feelings and desires. Never set two stanzas in different moods to the same music and try to heighten dramatic tension using musical motives associated with a person or incident.”

It was these musical tenets that were on full display in his new opera, La Jolie Fille de Perth. The contract for the opera was signed in July of 1866. Bizet said the libretto was the worst of his life—having to take liberties to make any kind of dramatic effect with the music.

This period is a prime example of Bizet’s productive prowess. Act I was finished by September. While composing the opera, he was correcting proofs for publishers, scoring waltzes and composing songs—all the while continuing work on his Roma Symphony.

The opera was completed in October and was sent to Carvalho on the 29th December—yet the production was delayed for one year. Bizet was furious:

“Rehearse or the law courts! If I die of worry, discouragement and also of hunger one of these fine days, it will occur to someone to do something about La Jolie Fille.”

It was finally premiered on December 26th, 1867—and Bizet was in very good spirits:

“I am completely happy! Never did an opera have a better start! The dress rehearsal produced a great effect! The piece is very interesting; the interpretation is most excellent! The costumes are rich! The settings are new! The director is a delight! The orchestra and singer are all of keenness! And what matters more than all that is the score of the Jolie Fille is a good piece of work! The orchestra gives it all a color, a relief, that I admit I didn’t dare hope for! I am sticking to my part. Now, forward! I must climb, climb, always climb. No more evening parties! No more fits and starts! No more mistresses! All that is finished! Absolutely finished! I am talking seriously. I have met an adorable girl whom I love! In two years she will be my wife! From now on nothing but work and reading; thinking is life! I am talking seriously; I am convinced! I am of myself! The good has killed the evil! The victory has won!”

The girl was Geneviève Halévy, the second daughter of Bizet’s old teacher. As with most events in Bizet’s life, the engagement was not without its drama. The Halévy family initially broke off the engagement, throwing Bizet into a fit despair:

"The hopes I have formed have been broken, the family has reserved its rights. I am very depressed. The blow I have received takes away all the hopes that were dear to me.”

It is unclear why the family took such a stance. Bizet said later that they regarded him as “a Bohemian and an outsider.” Nevertheless, they were eventually married in June of 1869.

Not only was La Jolie Fille de Perth well performed; it was, more importantly…well received.

“My work obtained a genuine and serious success! I was not hoping for a reception so enthusiastic and at the same time so severe…..I have been taken seriously, and had the great joy of moving and flipping an audience that was not predisposed in my favour……The press is excellent! Now, are we going to make money?”

This time around, the press was indeed congenial, declaring the opera a masterpiece from beginning to end. Unfortunately, this did not spare the opera from suffering a similar demise as The Pearl Fisher. The opera had only eighteen performances and disappeared from the Paris stage until 1890.

His musical activities over the next three years were…perplexing. He began at least eight operas–only completing one: La Coupe du Roi de Thule. While working on that opera, he at long last finished Roma, which was finally performed on 28th February, 1869 under the title Fantaisie Symphonique: Souvenirs de Rome. Bizet’s report was enthusiastic:

“First movement: a round of applause, some hisses, second round, a whistle, third round. Andante: a round of applause. Finale: great effect, applause three times repeated, hisses, three of four whistles. In fact a success.”

Despite its positive reception, the Symphony was largely ignored by the press. It was not heard again until five years after Bizet’s death in 1880, the same year it was published under the title Roma.

Act VI

On June 3rd, 1869 Bizet married Geneviève Halévy. By all accounts, the early months of the marriage were happy ones. The newlyweds were very much in love. But already there was friction on the horizon.

Geneviève had a history of nervous and mental instability which she inherited from both parents. Her mother, Leonie Halévy, regularly suffered periods of insanity which forced the family to have her confined.

Geneviève came from a tragic childhood. Her father passed away after a long illness when she was thirteen. Two years later her sister died suddenly at the age of twenty. Leonie, in an episode of mental derangement, accused Geneviève of being responsible for her death. As a result Genevieve could no longer live with her mother.

Her diaries show she was a young girl haunted by fear and dread of the future. This resulted in constant demand for support and reassurance, especially from her new husband.

His first major endeavor after his marriage was the completion of his father-in-law’s biblical opera Noé. After several fruitless attempts, the work was completed in October 1869. Also, in collaboration with the Opéra Comique, Bizet began work on three opera projects, in the end none of them completed. These were Calendal, Griselidis and Calrissa Harlowe. Unfortunately, all of his opera plans came to an abrupt end with the break-out of the Franco-Prussian war.

In July 1870, Napoleon III, provoked by Bismarck, declared war on Prussia. Within a few short weeks, the Second Empire had fallen; the emperor himself imprisoned and Paris besieged.

Bizet's reaction was immediate:

“What will become of our poor philosophy, our dreams of universal peace, world fraternity and human fellowship?! Instead of all that we have tears, blood , piles of corpses, crimes without number or end! I can’t tell you, my dear friend, in what sadness I am plunged by all these horrors. I remember that I am a Frenchman, but I cannot altogether forget that I am a man. This war will cost humanity five hundred thousand lives. As for France, she will lose it all!”

As a Prix de Rome winner, Bizet was exempt from the military; regardless, a few days after war broke out Bizet enlisted in the sixth battalion of the National Guard. He remained with his wife in Paris throughout the months of siege, which ended with the armistice on 26th January, 1871.

With the future of theatre in post-war France uncertain, Bizet resumed work on Griselidis and Clarissa Harlowe, while also dealing with many personal problems. including Geneviève suffering another nervous breakdown. It seems at this point, composing was a distraction from the many trials that life had thrown his way.

The Opéra Comique was now under the joint management of two very different characters: Adolph de Leuven, a true-blue conservative and Camille du Locle, who was more interested in exoticism, poetry and the symphonic elements.

Of the two, it was Du Locle who, wishing to attract up and coming young composers made Bizet his mission, offering him the libretto to Djamileh, a work based on Alfred de Muttet’s Namouna. Bizet was advised to get started at once.

Initially he found the subject “charming but horribly difficult,” but later wrote:

“It’s very distinguished, very noble, artistically very significant; it will enable me to be not entirely forgotten by the public and will at the same time, I hope, be good for business.”

He composed the score in a few weeks. A delightful accord has been left of Bizet during its composition:

“He walked about in a straw hat and loose jacket with the easy assurance of a country gentleman, smoking his pipe, chatting happily with friends, receiving them at table, with a conviviality that always had a touch of banter in it, between his charming young wife and his father, who was his host spent all day gardening as a change from the fatigue of giving lessons.”

Aside from Djamileh, Bizet was also working on a small yet delightful work of twelve pieces for piano duet entitled Jeux d’enfants, later orchestrating five of these charming pieces…

Act VII

After many delays and endless frustration, Djamileh was finally produced on 22 May, 1872. Sadly, it was not the success Bizet had hoped for. No details were spared for the settings and costumes; however, the singers were grossly subpar.

By the end Bizet was a complete wreck:

“There, a complete flop!”

The scene from the audience was amusingly described:

“It’s infamous! It’s odious! It’s very funny! What cacophony! What audacity! He’s making fun of us all! That’s where the Wagner cult leads to—to madness. Neither tonality nor shape nor rhythm! It’s no longer music—it’s macaroni. What! It is Italian music then? Not a bit, I mean it has neither beginning nor end!”

Djamileh lasted for eleven performances and then disappeared until the Bizet centenary in 1938.

Despite Djamileh being generally panned, Bizet felt proud of his work:

“What gives me more satisfaction than the opinion of these gentry is the absolute certainty of having found my path. I know what I am doing. I have just been ordered to compose three acts for the Opéra Comique. It will be gay, but with a gaiety that permits style.”

Although the subject was not yet chosen, this was the genesis for Carmen.

On the 10th of July, Bizet’s son Jacques was born and, shortly after, his next commission arrived. Carvalho, the former director at the Opera Lyrique, had migrated over to vaudeville, where straight plays were the flavor of the day.

Not wishing to sever his connection with music, Carvalho revived the melodrama–a play with incidental music - and invited Bizet to write the score for Alphonse Daudet’s L'Arlésienne. From this, a masterpiece was conceived in a matter of weeks. Bizet’s collaboration with Daudet was one of pure bliss.

Bizet began work on Carmen in January, 1873 with the goal of beginning rehearsals in October.

“I feel that the hour for production has come, and I do not want to lose a day.”

Ultimately, things were pushed until August 1874. Bizet left the country to finish the score–settling in Bougival, a quiet spot on the Seine. It was there Carmen was finished: 1200 pages of full orchestration in just under two months. Bizet was indeed pleased:

“They make out that I am obscure, complicated, tedious, more fettered by technical skill that lit by inspiration. Well, this time I have written a work that is all clarifying and vivacity, full of color and melody. It will be amusing.”

Celestine Galli-Marie was history’s first Carmen in 1874. A great admirer of Bizet’s music, she was very much struck by the part; and Bizet was equally struck by her suitability for the role.

The backstage gossip at the Opéra-Comique was that the two had a love affair as well as frequent quarrels. There is no evidence of this although Bizet’s marriage was very unhappy at this time and husband and wife were living apart.

It was a very trying four months of rehearsals for Bizet. Until the opera showed signs of success, he was met with a great deal of hostility from inside the theater. The orchestra resented the score’s difficulty, deeming certain parts unplayable.

The chorus were of the same mind, complaining that the music was impossible as they were required to both act and watch the conductor.

The first performance took place on the 3rd of March and the reception was disappointing. A brief report was left by Ludvico Halévy:

“Act I was well received: Galli-Marie’s first song applauded. End of the act good—applause. A lot of people on the stage after this act. Bizet surrounded and congratulated.

The second act less fortunate. The opening very brilliant. Great effect from the Toreador’s entry, followed by coldness, From that point on, as Bizet deviated more and more from the traditional form of opera-comique, the public was surprised, discountenanced, perplexed. Fewer people around Bizet between acts. Congratulations less sincere, embarrassed, constrained.

The coldness more marked in the third act. The only thing applauded was Micaela’s aria, of old classical cut. Still fewer people on the stage. And after the fourth act, which was glacial first to last, no one at all except three or four faithful and sincere friends of Bizet. They all had reassuring phrases on their lips but sadness in their eyes. Carmen had failed.”

When Bizet was congratulated by a fellow musician, his reaction was direct:

“I sense defeat. I foresee a definite and hopeless flop. This time I am really sunk.”

When another symphonic friend muttered the word success, Bizet replied:

“Success! Don’t you see that all those bourgeois have not understood a wretched word of the work I have written for them?”

To say that the libretto and the music of Carmen caused pandemonium in the press might be a bit of an understatement. The general consensus: Carmen is too obscene to be staged!

It was said that Galli-Marie over-emphasized the steamy side of her character to such an extent that:

“It would be difficult to go further without provoking the intervention of the police.”

The opera was accused of having more scandal than truth, it being:

“A vulgar opera-comique with a dash of the pathetic and a fine murder that is almost inexplicable.”

The fact that Carmen had only 48 performances is not really telling of its true success in 1875. In fact, it was nearly taken off the stage after five performances due to poor support. However, two things kept it afloat: a tempting rumor that it was a shocking performance to watch, and Bizet’s life tracking a final dramatic turn.

Late in March, 1875, Bizet had yet another attack of angina, but this was unlike the others: it was slow and incomplete and was accompanied by extreme depression. He was still deeply scarred over Carmen, exclaiming to a friend:

“Ah! I’ve had enough of writing music to surprise three or four comrades who then go and scoff behind my back!”

A close friend found him “torn between the raging desire to curse his judges and his terrors of believing them.”

Others observed that he was haunted by the fear of an early death.

The chain of events of the last few days of Bizet’s life are chronicled as follows:

It was said the husband and wife left for Bougival on May 28th. The first day went well: they walked hand-in-hand along the Seine and Bizet enjoyed an afternoon bath in the river.

On the 30th, Bizet suffered a violent and incapacitating attack of rheumatism, accompanied by high fever, great pains and depression. Partial recovery was followed on June 1st by a severe heart attack. A doctor was summoned on the morning of June 2nd declaring the crisis was over and prescribing strict bedrest.

Suffering throughout the day with a high fever, the doctor was again sent for but by the time he arrived, it was too late. Bizet died at 2am on June the 3rd, two hours after the curtain had fallen on the 33rd performance of Carmen and on his 6th wedding anniversary. Although the cause of death was never confirmed, it is largely believed that it was a cardiac complication of articular rheumatism.

The funeral took place on June 5th and was attended by more than 4000 people. Excerpts from Carmen and The Pearl Fishers were played on the organ; A makeshift orchestra performed his Prelude from L’Arlesienne, as well as Chopin’s Funeral March. Vocal numbers included the Agnus Dei and Pie Jesu from Act I of the Pearl Fishers.

A wreath was placed from the young competitors of the Prix de Rome, who could not be present due to examinations. He was interred in Père Lachaise cemetery. The special performance of Carmen that evening was unbearably moving and for the whole proceeding week Bizet was proclaimed “a master.”

It is an interesting fact that the day before his death, Bizet signed a contract for Carmen’s production in Vienna. It is this production–which was praised by Wagner and Brahms–that its true success dates.. It soon triumphed in St Petersburg, London, Dublin and New York.

After many metamorphosis, Carmen was finally accepted by Paris society in 1883, with Galli-Marie at the helm, Carmen’s original Carmen. It was Tchaikovsky who prophesied that within ten years Carmen would be the most popular opera in the world; and indeed, it was and remains so to this very day.

Credits

Written and edited by Kris Epps

Additional editing by Ashley Daniel Foot and Mack McGillivray

Music Supervisor and Clearances: Kris Epps and Ashley Daniel Foot

Sound design by Kris Epps

Associate Producer: Vincent Huynh

Voice cast:

Bizet: Felix LeBlanc

Narrator: Jane Potter

Additional Voices: Ashley Daniel Foot, Travis Baugh Allen, Vincent Huynh

Kris Epps - Over the past ten years, as an award-winning classical pianist Kris Epps has devoted more and more time to accompanying vocalist and instrumentalist, conducting choirs and instrumental ensembles, as well as directing musical theatre productions. As the artistic director of Cantiamo Choral Ensemble in Montreal and the former assistant conductor of the McGill Choral Society, he has performed dozens of well-received concerts.

Kris holds a degree from the Faculty of Music at McGill University. He has studied with Dorothy Morton, Iwan Edwards, Lauretta Altman among others, and at the Golandsky Institute Symposium at Princeton University.

Jane Potter - Jane holds an MA in Critical and Creative writing from the University of Gloucestershire, and loves telling stories in all forms: She lives in Victoria, and when she isn’t busy reading and writing, she can be found running a small business, baking in the kitchen, or weeding the garden.

Felix Leblanc - Felix LeBlanc is an award-winning actor, singer, dancer, and multi-instrumentalist. He is a graduate of the Canadian College of Performing Arts, has trained in Clown at the Manitoulin Conservatory for Creation and Performance, stage managed operas and musicals, holds a certification in stage combat from Fight Directors Canada, DJ’d his own radio show, composes and arranges original music, and plays an ever increasing list of instruments.

Ashley Daniel Foot - Ashley is Vancouver Opera’s Director of Engagement and Civic Practice and host of Inside Vancouver Opera. Boundlessly creative and fascinated by the way that art is created and presented, Ashley has guided arts organizations across Canada to craft messages and tell unique stories.

Mack McGillivray - Inside Vancouver Opera is produced by Mack McGillivray, an audio producer creating shows for radio and podcast. He is passionate about cultivating local community and a lifelong lover of opera.