An essay by Ryan McDonald

Vancouver Opera is presenting Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream for the first time in our history. As part of our work in exploring and explicating the opera, we have commissioned some artists and writers to explore their responses to the opera. More information on our production is here.

Benjamin Britten, arguably the most prolific composer of the 20th Century is credited with reviving the tradition of English Opera, having composed 18 operas during his illustrious career. More remarkable perhaps than his numerous musical accomplishments, was his ability to live openly as gay man (as open as one could live during a period where homosexuality was criminalized) and maintain the respect of British musical, political and social echelons.

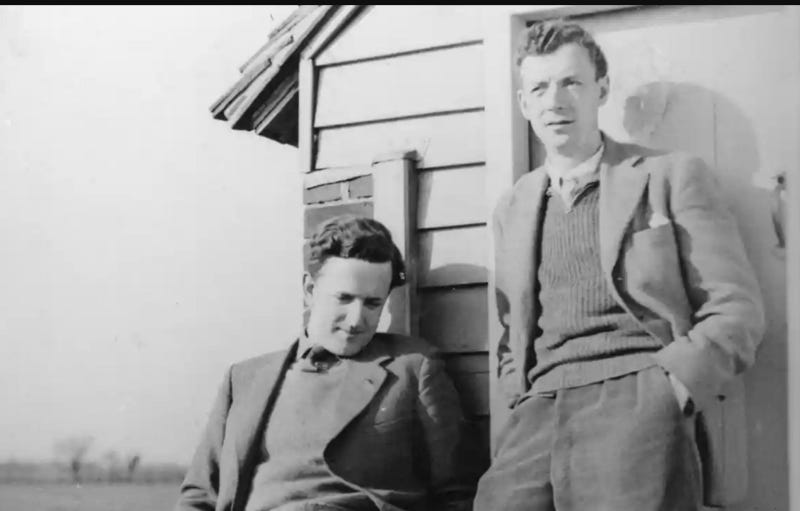

Not one for the spotlight and a self described pacifist, Britten was a revolutionary figure for both queer audiences and musicians alike. This revolution was quiet, and it took a keen eye to discern, but Britten’s not so subtle subtext, written so seamlessly into the very fabric of his musical works, was a waving rainbow flag in the face of the homophobic society Britten and his peers were operating within. His closest “peer”, Peter Pears was Britten’s longtime partner, collaborator, muse and inspiration. Their relationship was so closely tied to Britten’s compositions, one can map the phases of their relationship by examining the roles written for Pears.

Britten’s Death in Venice, which premiered in 1973, most directly speaks to his life as a queer man. The pain and frustrations an aging gay man faces grappling with his sexuality are on full display. It may be the fact that this was Britten’s last opera or that the composer would be dead within three years of its premiere, but this work is arguably Britten’s most vulnerable.

If Death in Venice is Britten at his most honest and direct, then A Midsummer Night’s Dream is the composer at his most scintillating and cunning. Every note of this ethereal score is queer coded, allowing the overtly sexual overtones in Shakespeare’s writing to come to life on stage.

After an opening chorus sung by the fairy children, the first voice we hear is that of a countertenor. The countertenor voice, which boasts a similar range to that of a contralto or mezzo soprano, has seen a favorable resurgence in the last half century, largely due to Benjamin Britten. While audiences today are far more accustomed to the countertenor voice, the audiences of 1960 would have certainly been surprised. Britten knew there would be limits to how he could highlight the relationship between Oberon and Puck. To ensure the King of the Fairies was every bit a fairy, he chose the countertenor voice, a traditionally ‘female’ sound coming out of a traditionally ‘male’ body.

The use of motifs are imperative to the tonal structure of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Britten gives the Lovers, Rustics and Fairies individual musical motifs, often played when they enter or exit a scene. The most challenging, flashy and recognizable motifs however are saved for Oberon and Puck. When one follows the stage directions, courtesy of Peter Pears, it becomes immediately clear that Oberon cannot so much as turn his head or send Puck on a mission without this movement be accompanied by a grand flourish. Each flourish grander than the last, and often played on the celeste, an instrument itself foreign to most orchestras, is Britten’s not so subtle way of indicating Oberon’s larger than life, flick of the wrist persona. Additionally, as the intensity builds between Oberon and Puck, the orchestra responds with the most sensual, dissonant and pulsating harmonies. So brilliantly personifying the always volatile and ever deeply passionate and sensual relationship shared between Oberon and Puck.

Benjamin Britten never hid his sexuality per se, and lived a long and largely happy life with his partner Peter Pears at a time when most queer men were being persecuted for their sexuality. He did, however, understand the climate in which he was creating and the audiences for which he was writing. Through Britten’s genius, he invented ways to allow his sexuality and the course of his relationship to be heard in his music.

Through his extensive operatic canon, I believe Britten has left a little something for every classical music listener. Additionally, the “King of English Opera” revolutionized the operatic countertenor voice along the way! I think it is imperative however, that we never lose sight of the context in which these works were created as I believe they allow the score to come to life in the most fulsome way.

And so I leave you with this. In 1974, just after Britten had undergone heart surgery, he wrote the following to Pears, “My darling heart (perhaps an unfortunate phrase, but I can’t use any other) … I do love you so terribly, not only glorious you, but your singing. … What have I done to deserve such an artist and man to write for? … I love you, I love you, I love you.”

Hailed by Opera Canada for his performance in Dido and Aeneas: “Ryan McDonald, a young Newfoundland and Labrador countertenor, made a particularly favorable impression as Spirit. McDonald has a voice of luminous, fresh colour, combined with natural musicality and an exciting sense of narrative drama”. A recent Encouragement Award winner from the Metropolitan Opera National Council Audition, Ryan McDonald has been seen on stage as Athamas in Handel’s Semele, First Witch and Spirit in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, L’enfant in Ravels L’enfant et les sortilèges, Cupid in John Blows Venus and Adonis and Jack in Sondheim’s Into the Woods.

In concert, Ryan has appeared as a soloist with the Newfoundland Symphony Orchestra, London Handel Orchestra, Theatre of Early Music, Hamilton Symphony Orchestra, Amadeus Choir, Symphony in the Barn, Nota Bene Players and Toronto Mendelssohn Choir.

During the 21/22 season, Ryan became Young Artist with Pacific Opera Victoria’s Civic Engagement Quartet. Additionally, they joined Confluence Concerts as their inaugural Young Artistic Associate.

Ryan is the co- founder of OperaQ, a company focused specifically on presenting queer theatre, by queer artists for queer audiences. Ryan led the reimagined production of Purcell’s Dido and Belinda as the titular character, Dido. In addition to their musical activities, Ryan is currently pursuing a DMA in Historical Performance at the University of Toronto where they are researching the life of Klaus Nomi and investigating the ever expanding queer performance practice guide.