an essay by

NICHOLAS BURNS

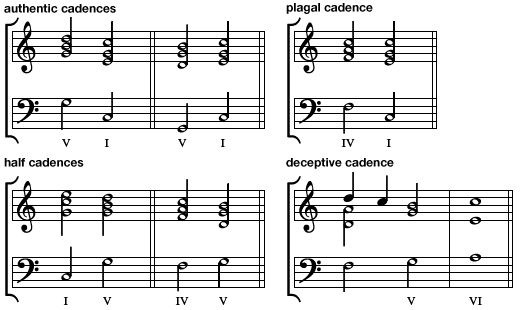

Writing these essays for Vancouver Opera is a lot of fun. My ‘day job’, singing countertenor almost entirely focuses on baroque music, and primarily the music of Handel and Bach. So being asked to write about Don Pasquale, a work about which I previously knew nothing, presented me with an opportunity to explore questions at which a seasoned Don Pasqaule/bel canto/Donizetti professional might scoff. I take musical ‘first impressions’ seriously, and the first thing that struck me when listening to Pasquale was its seemingly incessant use of what I’m calling the ‘ba-dum, ba-dum, ba-dum’ ending (from here on written as BD3). For those with a music theory background, this is a cadential section at the end of an aria with repeated V-I cadences. For those who are fortunate enough to have been spared years of music theory, it sounds like this.

The BD3 ending is a universally understood musical way of saying “the end.”

But where did the BD3 ending have its beginnings? And why does Donizetti use it so often in Pasquale?

The where is easy enough to trace. By the end of the baroque era in the 1750s the da capo (‘from the head’) aria in which the performer sings a first section, a second section, and then returns to sing the first section again, reigned as the supreme musical form on the opera stage.1 This ABA structure allowed performers the perfect opportunity to show off by adding extravagant ornamental notes to the score.

Composers would write da capo at the end of an aria, saving them the time of having to write out the entire first section of the aria again. This musical return, the da capo, was by all accounts, well loved by the audiences.2 However, composers of the early classical era, such as Mozart and Haydn, eventually grew tired of the da capo aria. By the time Donizetti was in full flight as a composer, he and his (probably more) famous contemporary, Giacomo Rossini adopted a new operatic aria form: the solita forma (‘conventional form’) with two sections: the cantabile featuring the melody, then the cabaletta, a fast part that allowed the singer to unleash, all followed by the BD3 ending.

Rossini was perhaps the most famous opera composer of the mid-nineteenth century bel-canto era and everything he touched was a financial success.3

“Donizetti [therefore] felt obligated to cater to his audience's tastes in his early years, that of Rossini.”4 And you guessed it, the BD3 ending that was Rossini’s calling card, became Donizetti’s, too.

Now begins the part of the essay where the scholarship ends, and my speculation, ahem, intuition, as a performer takes over in order to answer the question: why was the BD3 ending so popular? I spent hours attempting to find scholarly materials to answer this question, so I could provide a nicely cited source to go “aha, dear reader, I’ve pieced together this musical mystery!”. Alas, there seems to be no such easy answer. However, a possible answer to the mystery of the BD3 ending lies in the popular music of today. Take for example, the trend of replacing wordy choruses in pop songs with a hard hitting dance break instead.5

Like our BD3 mystery, the question of where the pop-music dance break comes from is quite clear: the proliferation of electronic dance music in pop. The question of why it became so popular is just as mysterious as that of the BD3; or perhaps just as dead simple: people like it. Just like a stirring dance chorus in today’s chart toppers, the BD3 ending appealed to opera goers tastes in the mid 1800s. A more contemporary example of this form would be the Beatles smash hit, Hey Jude. The first section is slow and melodic, the last part, the “na na na’s” is a riff over simple harmonies, exactly the same as Donizetti’s cabaletta sections. Simple harmonies, high energy orchestration, and high energy singing. Sounds a lot like our BD3 ending….!

If this essay is meant to glean a truth for its readers, here it is: opera goers love crazy singing.

Be it nine high Cs,

or the Queens high Fs in The Magic Flute,

or Norina’s aria in Don Pasquale, So anch’io la virtù magica, we love over the top vocal fireworks.

Pasquale provides the perfect palate for singers to unleash thanks to the solita forma arias and those rousing ba-dum, ba-dum, ba-dum endings. But don’t just take my word for it, experience the thrill for yourself, and do go see Vancouver Opera’s production of Don Pasquale!

Vancouver-based Countertenor Nicholas Burns appeared at the Britten-Pears Young Artist Programme, performing Bach cantatas with Philippe Herreweghe. He has also appeared with appeared with the American Bach Soloists, BachFest Leipzig, Tafelmusik, Arion Baroque Orchestra, Early Music Vancouver, Corona del Mar Baroque Music Festival, L’Harmonie des saisons, The Theatre of Early Music, and le Studio de musique ancienne de Montréal. On the opera stage, Nicholas has performed in numerous Handel operas including Cesare in Handel’s Giulio Cesare, Bertarido in Rodelinda, Polinesso in Ariodante, and Lichas in Hercules. He also gave the world premiere of the opera L’Orangeraie by French composer Zad Moultaka. Nicholas frequently performs the vocal works of JS Bach, including over 50 of Bach’s cantatas, as well as the St. Matthew Passion, St. John Passion, and B Minor Mass in a ‘one-voice-per-part’ setting. Upcoming performances include engagements with Tafelmusik, Arion Baroque Orchestra, Toronto Bach Festival, Symphony Nova Scotia, Oberlin Conservatory, I Musici, and Early Music Vancouver. Aside from singing, Nicholas is an accomplished bagpiper, having won the World Pipe Band Championships in 2012.

Westrup, Jack. "Da capo." Grove Music Online. 2001.

Burney, Charles. 1969. The Present State of Music in France and Italy. New York: Broude Bros.

Rothstein, William. “Tonal Coherence in Rossini’s Italian Operas.” In The Musical Language of Italian Opera, 1813-1859. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022

Ashbrook, William. Donizetti. London: Cassell, 1965.

Spicer, Mark. “(Ac)Cumulative Form in Pop-Rock Music.” Twentieth-Century Music 1, no. 1 (2004): 29–64.